How to think about programs & programming? ABIYZ: inspired by age old tools like arithmetic.

Problem Statement

A compiler catches errors and more importantly guides us towards syntactically valid programs. Is there a similar guide for thinking about programs & programming? Some thing/process that can help us design systems & program them better ?

A thought experiment example

Ultimately, programs transform inputs to outputs. Those inputs and outputs have some meaning to humans. Such transforms are common even outside programming; that is, in the real world. We don’t think twice when performing such transforms, but we can learn something by examining one such example in depth.

Problem

Work Desk Area in English: Calculate the surface area of your work desk and express it in words, likeForty TwoorSixteen.

Your solution likely goes like this:

- Model the work desk as a rectangle.

- Measure the lengths of sides of the desk and consider them to be the rectangle’s dimensions

- Capture the dimensions in

PVDS(Place Value Decimal System). Other systems would be possible, for example, binary.

- Capture the dimensions in

- Compute the area using Rectangle’s area formula.

- Perform a multiplication of the dimensions in PVDS using some multiplication algorithm

- The area is now available in PVDS

- Take the area in PVDS and announce it in words

We can even generalize the solution approach.

flowchart TD

A[Input] -- Transform --> B[Input]

Y[Output] -- Transform --> Z[Output]

subgraph psd ["Problem Solving Domain"]

B -- Solve --> Y

end

subgraph rwd ["Problem Domain"]

A -. Overall Transform .-> Z

end

psd ~~~~~ rwd

In the Work Desk area in English, the Problem Solving Domain (i.e. the abstract world) is Geometry & Arithmetic.

flowchart TD

A[Work Desk] -- Transform --> B[Height & Width in PVDS]

Y[Area expressed in PVDS] -- Transform --> Z[Forty Two]

subgraph psd ["Domain: Geometry & Arithmetic"]

B -- Multiplication --> Y

end

subgraph rwd ["Domain: Work Desk, Words like Forty Two"]

A -. Work Desk area in English .-> Z

end

psd ~~~~~ rwd

We can generalize a pattern of problem solving from the thought experiment:

- To solve a problem, we need to utilize general tools (like geometry, arithmetic)

- The tools are abstract, human-invented things and only work with human-invented concepts

- For example, numbers, place value decimal systems, rectangles, multiplication are all abstract concepts/tools

- There’s an abstraction corresponding to Input & Output within each of the two domains, Problem domain & Problem solving domain

- In the Problem domain, the Input is the Work Desk and the output is English words

- In the Problem Solving domain, Input is length & breadth of a rectangle (in PVDS) and the output is an Area (in PVDS)

- To solve the problem, the following steps are followed

- Input from Problem Domain is converted to Input in Problem Solving Domain

- The problem is solved in the Problem solving domain

- The

Work Desk Areaproblem is solved by multiplying the length & breadth- Output from Problem Solving Domain is converted to Output in Problem Domain

ABIYZ pattern

Let’s name this pattern of problem solving since we’ll refer to it later. Let’s call it ABIYZ (for reasons not explained here).

Good scientific laws lead to inferring other scientific laws. For example, Ole Roemer inferred that light had finite speed. He deduced this from the observations that eclipses occur at different times than predicted based on Earth’s distance to Jupiter. He held that planetary laws were immutable and looked for a different explanation of the observations.

Similar to Roemer’s method, we too would like to hold some tenets of software engineering as immutable so that we can discover others when something doesn’t quite make sense. What are those tenets? Just like the compiler only allows syntactically valid programs, these tenets should lead to clean, explainable programs.

I’ve been using ABIYZ as one of those immutable tenets and my experience has been very pleasant. It has helped me in designing clearly and avoiding sphagetti mess in code. I have also found it helpful to understand large frameworks.

Relevance for Software Engineering

In the Work Desk example, we used a Problem Solving Domain already available for us (arithmetic, geometry) where as in programming, we need to invent the Domain and the tools ourself.

Good software engineering requires inventing the concept of Place Value Decimal System and the Multiplication algorithm to solve the Work Desk Area problem. Numbers and arithmetic is a good problem solving domain for the area problem.

Different problems will require different domains. Let’s see some examples.

Example 1

Let’s consider implementing the eval function.

| Type | Description |

|---|---|

| Input | An expression String, like (42 * 5) + 3 |

| Output | The evaluation result, in words |

| Function signature | String eval(String expression) |

| Example | eval("(42 * 5) + 3") returns "Two Hundred And Thirteen" |

To use the ABIYZ pattern,we need to answer a few questions:

| Question | Answer |

|---|---|

| How’s the input modeled in the PSD (Problem Solving Domain) ? | Expression Tree |

| How’s the output modeled in the PSD? | long |

| How is “Solve” modeled in PSD? | evaluateTree function |

| What transforms the Input to PSD from PD? | parse function |

| What transforms the Output to PD from PSD? | toWords function |

flowchart TD

A["`Expression String, e.g. 42*5+3`"] -- parse --> B["`**Expression Tree**,

e.g. +( *(42, 5), 3)`"]

Y[long, e.g. 213] -- toWords --> Z[English words, e.g. Two Hundred and Thirteen]

subgraph psd ["Problem Solving Domain"]

B -- evaluateTree --> Y

end

subgraph pd ["Problem Domain"]

A -. Evaluate expression & output result in English.-> Z

end

psd ~~~~~ pd

Once the ABIYZ questions are answered, we can model the classes & implement the functions:

- Classes

ExpressionTree

- Functions

ExpressionTree parse(String input)long evaluateTree(ExpressionTree exprTree)String toWords(long value)

The ExpressionTree class is straightforward

// An ExpressionTree is either of

// Addition, Multiplication or just a Number.

sealed interface ExpressionTree {

record Addition(Expression left, Expression right) implements Expression {}

record Multiplication(Expression left, Expression right) implements Expression {}

record Number(long value) implements Expression {}

}

The overall eval function is trivial:

String eval(String expression) {

return toWords(evaluateTree(parse(expression));

}

The other functions are straightforward too (use any parser combinator or grammar tools for parse function) and we won’t implement them here.

KEY IDEAS

- Asking the ABIYZ pattern questions can shed insights on how we think about the problem

- We invented new concepts (

ExpressionTree) to simplify solving the problem - As a bonus, the solution is clean and can be reused effectively. For example, many pieces can be reused for variations of the original problem:

- Instead of outputting English Words, output Spanish words

- Change the

toWordsfunction totoSpanishWords,toEnglishWordsetc. Other functions don’t need to change

- Change the

- Instead of accepting a String expression, accept a visual input (i.e. need OCR)

- Change the

parsefunction toparseOCR. Other functions don’t need to change

- Change the

- Instead of outputting English Words, output Spanish words

Example 2

For this example, we’ll diff two json documents, the jsonDiff function.

| Type | Description |

|---|---|

| Input | Two Json Strings |

| Output | A String capturing the diff result (see below) |

| Function signature | String jsonDiff(String leftJson, String rightJson) |

// Diff output format

leftJson = {

equal: 42

unequal: 1

leftOnly: "abc"

child: {

equal: 42

leftOnly: "abc"

}

equalChild: {

a: 1

b: "bcd"

}

longString: "aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa"

}

rightJson = {

equal: 42

unequal: 2

rightOnly: "xyz"

child: {

equal: 42

rightOnly: "xyz"

}

equalChild: {

a: 1

b: "bcd"

}

}

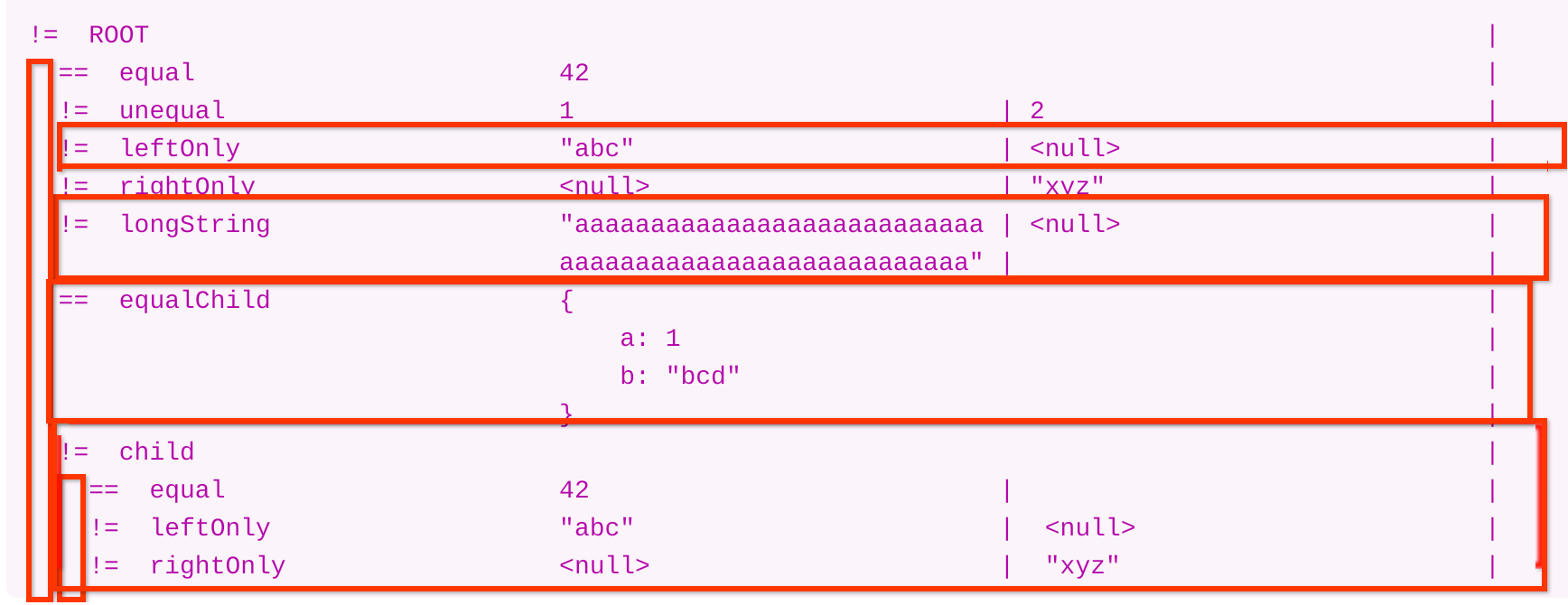

jsonDiff(leftJson, rightJson) returns the following diff output:

!= ROOT |

== equal 42 |

!= unequal 1 | 2 |

!= leftOnly "abc" | <null> |

!= rightOnly <null> | "xyz" |

!= longString "aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa | <null> |

aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa" | |

== equalChild { |

a: 1 |

b: "bcd" |

} |

!= child |

== equal 42 |

!= leftOnly "abc" | <null> |

!= rightOnly <null> | "xyz" |

For simplicity of exposition, let’s ignore List typed members of the Json (they don’t change the story).

The rules of the diff strings are:

- There are 4 columns of the output, each of a fixed width.

- Indicator, like

==or!= - Property name, indented, like

ROOT.child.leftOnly - Property value on the left side; displayed when there’s a diff

- Property value on the right side; displayed when there’s a diff

- Special case: When property values on both sides are equal, display it after merging the columns of the left & right sides

- Special note: There’s a separator

|between left and right side columns unless they are merged.

- Indicator, like

- Each property will have one horizontal entry (it could span multiple lines like

equalChild) - Equal properties have their values displayed. E.g.

equalChildandequalproperties - Inequal properties have both sided values displayed. E.g.

unequal - Properties that occur on only one side should have their values displayed. E.g.

leftOnly&rightOnly. The special<null>indicates lack of value for the property. For example, there’s no property namedleftOnlyon the right side

To use the ABIYZ pattern,we need to answer a few questions:

| Question | Answer |

|---|---|

| How’s input json modeled in the PSD (Problem Solving Domain) ? | Using JsonObject |

| How’s the output modeled in the PSD? | TextBlock |

| How is “solve” modeled in PSD? | diffJsonObjects function |

| What transforms the Input to PSD from PD? | jsonParse function |

| What transforms the Output to PD from PSD? | TextBlock.toString() method |

flowchart TD

A["`(Json string, Json string)`"] -- jsonParse --> B["`(JsonObject, JsonObject)`"]

Y["`**TextBlock**`"] -- TextBlock.toString() --> Z[diff string]

subgraph psd ["Problem Solving Domain"]

B -- diffJsonObjects --> Y

end

subgraph pd ["Problem Domain"]

A -. Diff two json strings & output them .-> Z

end

psd ~~~~~ pd

We’ve just invented two concepts that we expect will make it easier to solve the problem: JsonObject & TextBlock. How do we go about defining them more clearly? We make a few observations:

-

JsonObjectshould have at least as much information as the input json strings -

TextBlockshould have at least as much information as the final diff string

What about the operations on these concepts? We make a few more clarifications:

- We create a different class for each of these concepts. Lets call them by the same name; so, we have two classes

JsonObjectandTextBlock - The Operations on our Concepts translate to methods on our Classes.

- The operations are guided by how

diffJsonObjectswill utilize these concepts.- In other words, we are designing the tools (the methods) so that we can utilize them to help solve the problem easier.

This gives us an outline already.

sealed interface JsonObject {

// A Json value which happens to be another json

record JsonStruct(Map<String, JsonObject> children) implements JsonObject {

// Obtain the value of a given property, if it exists

Optional<JsonObject> getValue(String propertyName) {...}

// When we compute the diff, we need to inspect every property

Iterable<Map.Entry<String, JsonObject>> allChildren() {...}

}

// A Json value which happens to be just an integer

record JsonInteger(long value) implements JsonObject {}

// A Json value which happens to be just a string

record JsonString(String value) implements JsonObject {}

}

Note how JsonStruct has methods that are used by diffJsonObjects.

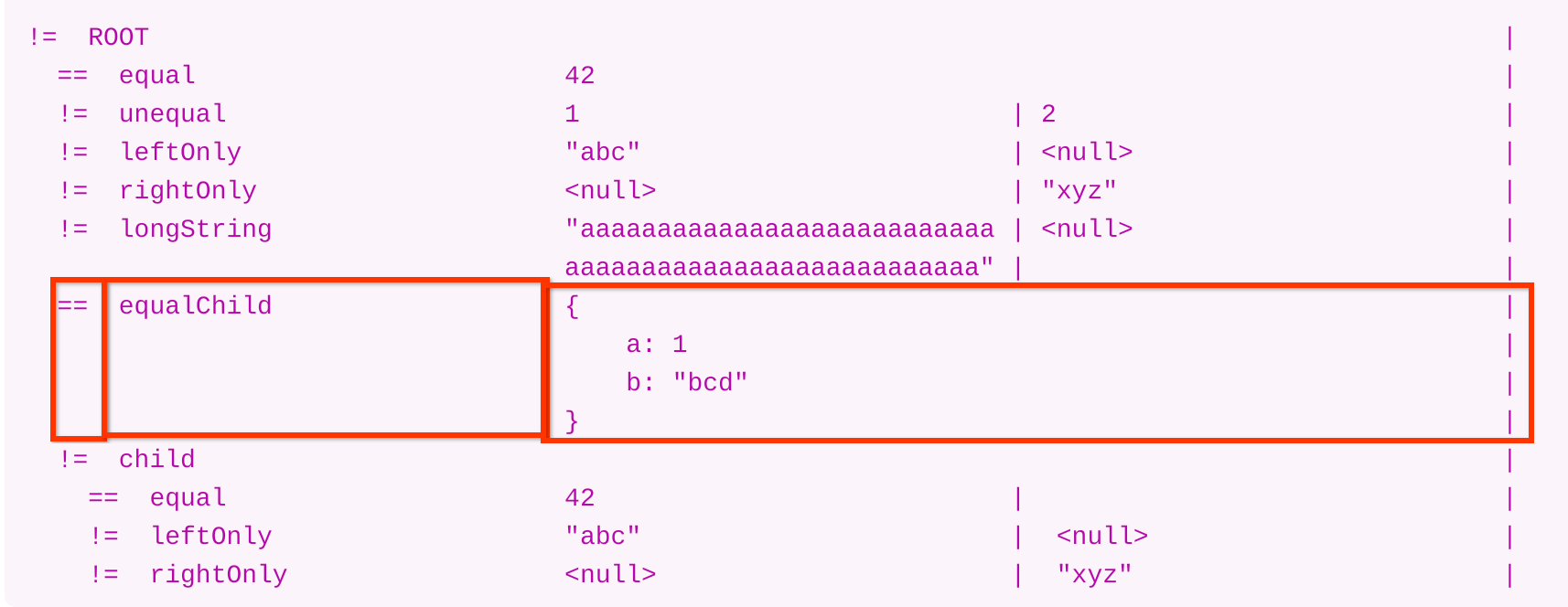

Now, let’s turn to TextBlock, which models the output diff string. Since it should capture the diff string, its structure should perhaps reflect the composition of the diff string. In other words, if we can express the diff string as being composed out of smaller individual units, we will have modeled TextBlock.

In this image, we can see that the overall diff is composed out of a stack of vertical blocks

Each of those vertical blocks is composed out of horizontal blocks

There’s recursive structure here & we won’t go into full details but we are now ready to model the TextBlock.

- A

TextBlockis a rectangular block of text - Two

TextBlocks can be combined either horizontally or vertically.

That’s all we need to produce the diff string. So, we can now convert it into a simple class definition & operations

interface TextBlock {

int height();

int width();

// Returns the list of lines that this TextBlock consists of

// There will be #height() such returned lines

// The size of each line will be #width() characters long

List<String> content();

}

final class TextBlockOperations {

// Appends two TextBlocks side by side and returns this newly appended one.

// Their top edges will be aligned.

// If their bottom edges don't align, the shorter one will grow downwards to align

TextBlock appendHorizontal(TextBlock left, TextBlock right);

// Appends two TextBlocks top to bottom and returns this newly appended one.

// Their left edges will be aligned.

// If their right edges don't align, the shorter one will grown to the right to align

TextBlock appendVertical(TextBlock top, TextBlock bottom);

// Returns a TextBlock with the specified width and the specified content.

// If the content is shorter than width, spaces are used to pad it to 'width'.

// If content is larger than width, the TextBlock will keep gaining new height

// to accommodate all of the content while never exceeding the width.

// So, for width = 3, content = abcdefg, the returned TextBlock will look like

// (excluding the enclosing | characters)

// |abc|

// |def|

// |g |

TextBlock create(String content, int width);

}

It is straightforward to implement all the relevant functions. In particular, diffJsonObjects can construct the finall diff TextBlock by composing it step by step using the composition operations from TextBlockOperations.

This example demonstrates how asking simple questions in the ABIYZ pattern enables us to write clean, modular, functional code. The fact that each of these concepts has its own classes means we can test them independently. For example, whether a TextBlock is implemented correctly has nothing to do with what it is used for (like the diffing here). In other words, the ABIYZ pattern encourages defining independent concepts which can then be tested separately.

Example 3

Consider a person communicating their thoughts with another person via text messaging. There’s ABIYZ hidden here too:

flowchart TD

A[Thought] -- Encode into SMS --> B[SMS message]

Y[SMS message] -- Decode into thought --> Z[Thought]

subgraph psd ["Problem Solving Domain"]

B -- Send SMS --> Y

end

subgraph rwd ["Problem Domain"]

A -. Communicate Thoughts .-> Z

end

psd ~~~~~ rwd

In fact, we can drill down into this example and ask: how are SMS getting transmitted?. We can again use ABIYZ to reason about it, recursively. SMS are transformed into a Stream of Bytes which are sent across the network. Again, we can ask, how are those bytes transferred? and so on so forth until we get all the way down to transistors, then atoms, then subatomic particles etc.

flowchart TD

A[Thought] --> B[SMS message]

B --> C[Byte Stream]

C --> D[EM Wave]

D -- transmit --> W

W[EM wave] --> X

X[Byte Stream] --> Y

Y[SMS message] --> Z[Thought]

subgraph four ["Electromagnetic waves"]

D

W

end

subgraph three ["Bytes"]

C

X

end

subgraph two ["SMS"]

B

Y

end

subgraph one ["Thoughts"]

A

Z

end

three ~~~~~ four

two ~~~~~ three

one ~~~~~ two

Example 4

ABIYZ also helps us understand software better. For example, understanding frontend frameworks like Angular (documentation) for a beginner can be difficult. But, it can help to think in ABIYZ terms.

Consider a website that shows a social media feed. The user sees some pixels corresponding to their social media feed. As the feed changes, the pixels change. Similarly, as the user interacts with the UI(filters/clicks etc), the feed changes. Angular aims to help manage this ping-pong. Looking at the Angular docs can be intimidating, but we can try to understand it better by asking the standard ABIYZ questions: what is the Problem Domain, the Problem Solving Domain and their corresponding concepts & operations?

Pretty soon, we get to the ABIYZ graph for a Button Click action. That is, when a user clicks a button, we want to update the UI in response. Typically, this will include fetching new data and/or changing the screen data/layout in response to the newly fetched data.

flowchart TD

A[Screen] -- Browser Sync --> B[DOM]

B -- Angular Sync --> C[Ng Template, App State]

C -- "Update App State (your code)" --> X

X[Ng Template, Updated App State] -- Angular Sync --> Y

Y[DOM] -- Browser Sync --> Z[Updated Screen]

subgraph three ["Angular"]

C

X

end

subgraph one ["Visual, Biomechanical"]

A -. Clicks a Button .-> Z

end

subgraph two ["Browser API"]

B

Y

end

one ~~~~~ two

two ~~~~~ three

Angular becomes easier to understand & retain once we understand the different domains (User’s senses, Browser, Angular). Angular simply models the DOM as a template with blanks filled from Application State (fancily called data binding). Your code to respond to the button then just needs to update the Application State and Angular is responsible for syncing it to the DOM. Of course, there is a LOT more to Angular than this, but asking ABIYZ questions provides a good start for understanding it more comprehensively.

Example 5

The Truth framework is a Fluent assertions for Java. It allows you to assert in tests, like:

@Test

public void test_restaurantQuery() {

// retrieve a restaurant by query

Restaurant restaurant = queryRestaurants("where menuItem contains 'Pizza'").firstResult();

// test that the query actually worked

assertThat(restaurant).containsMenuItem(Pizza);

}

At first glance, assertThat(restaurant).containsMenuItem(Pizza) looks somewhat magical. But, ABIYZ again helps us understand.

flowchart TD

A[Restaurant object] -- toSubject() --> B[RestaurantSubject object]

B -- containsMenuItem(Pizza) --> Y["Boolean (is requirement met?)

&

Failure message (if requirement not met)"

]

Y -- assertTrue() --> Z[Requirement asserted.]

subgraph one ["Domain: Regular Objects"]

A -. Assert requirement that

menu contains Pizza .-> Z

end

subgraph two ["Domain: Truth Subjects"]

B

Y

end

one ~~~~~ two

Essentially, <X>Subject is a new domain which readily verifies custom conditions on <X>. Here, <X> is Restaurant. For example, if <X> = List, ListSubject will have methods that are relevant for verifying the state of the list (but not present in the List class itself), such as hasElementsExactlyInOrder(elements), so you can write myListSubject.hasElementsExactlyInOrder(1,2,3). The ListSubject is reusable across every test class and can provide a ton of methods for typical condition verification.

Using the standard ABIYZ pattern, similar to Example #1’s toWords(evaluateTree(parse(expression)), we can now write assertTrue(containsMenuItem(toSubject(restaurant), Pizza)). From there, it is a refinement of the API to make it fluent & more user-friendly.

| Different refinements of the assertion API | Comment |

|---|---|

assertTrue(containsMenuItem(toSubject(restaurant), Pizza)) | standard ABIYZ format |

assertTrue(toSubject(restaurant).containsMenuItem(Pizza)) | containsMenuItem became a method on the Truth subject.This method is very natural for verifying a Restaurant’s properties, but it should not be present on the Restaurant class itself because it is not a top-level property. |

assertThat(restaurant).containsMenuItem(Pizza) | A more fluent version of the same content |

In the actual Truth subject design, <X>Subject encapsulates not just the object being verified, but also the Failure strategy (quick exit vs report lazily). Hence assertThat(restaurant) is really a shortcut for new RestaurantSubject(restaurant, failureStrategy = ASSERT). In addition, each method can customize the error message; for example the error message for containsMenuItem(Pizza) should be different from that of hasFoodInspectionGrade(A). In short, the Truth Subject domain has the tools & concepts required for verifying conditions on objects in tests.

Setting aside the details, this is another example where ABIYZ helps us understand a framework.

Summary

The purpose of abstraction is not to be vague, but to create a new semantic level in which one can be absolutely precise. - Dijkstra

Perhaps the spirit of the ABIYZ pattern is succinctly captured by the Dijkstra quote. It encourages thinking in terms of different domains. Each domain has its own set of concepts and tools. We solve problems of one domain by modeling them as problems in another domain where they are more readily solvable. For a SWE, the challenge is to identify and create these domains in service of the problem at hand. The diffJsonObjects example demonstrated this thought process.

To conclude, ABIYZ pattern of problem solving is a useful thought tool that can simplify designing clean, well-factored, well-tested programs for certain classes of programs. It is likely that software engineers are doing this very particular thing, but in an intuitive way when designing programs/systems. ABIYZ formalizes it so that we can approach even difficult problems logically.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: